This is paragraph text. Click it or hit the Manage Text button to change the font, color, size, format, and more. To set up site-wide paragraph and title styles, go to Site Theme.

My daughter, currently nearing completion of a graduate program in counselling, recently introduced me to the term “ambiguous loss”. This term applies to a loss that is unclear and lacks certainty, leaving family members and close friends feeling stuck because it is so difficult to mourn or find closure. One type of ambiguous loss is when the person is

physically present but psychologically absent because their personality, memory, cognition, or emotional connection has been altered. Examples might include a family member with dementia, a progressive disease, a severe emotional disorder, or substantial brain injury. A second type of ambiguous loss is when the person is

psychologically present but physically absent. This could include a missing person due to a natural disaster, a long- term incarceration, a kidnapping, or severe estrangement from the family. This type of loss can lead to intense confusion, frozen grief, and a prolonged sense of helplessness.

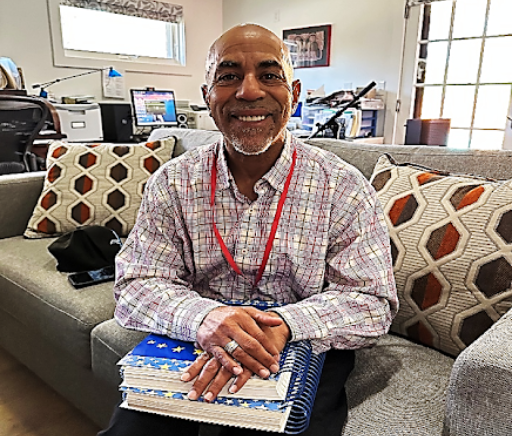

As the father of a young man who sustained a severe brain injury over seventeen years ago (at age 20) and has continued to live an extremely limited life ever since, I find this term quite descriptive of what I have experienced. Prominent issues that family members may be vulnerable to as the result of ambiguous loss are:

- Lack of closure: Without a death or clear end, there are no traditional mourning rituals to help process the loss.

- Frozen grief: The uncertainty prevents the grief process from moving forward, leaving people in a constant state of limbo. When grief cannot be fully expressed it can lead to guilt and despair.

- Realism versus hope: In past paradigms, this conflict may have been labelled “acceptance versus denial”. Some friends/helpers may urge “realism” (that is, acceptance) while others urge “hope (that is, denial). But a balance between the two may be necessary to clearly perceive the present situation and also keep doing what you believe may lead to a better future outcome.

- Social misunderstanding: Others may not understand the pain or recognize the loss since there is no physical absence, making it difficult to get support. Family members’ social interactions or social availability may be curtailed because of feelings of shame, depression, resentment, or even basic practical factors which inhibit scheduling for socializing.

- Impact on daily life: It can be hard to make decisions about the future when the present is so uncertain, leading to feelings of being immobilized, exhausted, and hopeless.

- Difficulty identifying and accepting negative feelings: Such feelings, if left unexpressed, can lead to sadness and self-recriminating thoughts. Underlying feelings of anger or resentment, even if irrational in some respects, would be better directed toward fate, a higher power, to another person or party thought to be responsible, or even to the “lost” person himself or herself. If identified and expressed, such feelings can be better understood and put into perspective to reduce distorted interactions and other troubling negative effects.

- Family dysfunction and disruption: The heightened stress that accompanies ambiguous loss can lead to conflict, disagreement, and argumentativeness among family members. Communication may falter as tension and distancing increase. Disruption in family routines may occur and expressions of support and affection within the family may lessen.

To clarify, not all families or family members who are experiencing ambiguous loss will experience these issues powerfully. But most, if not all, families are vulnerable to these kinds of issues showing up in some form given the intensity of experiencing ambiguous loss.

Open communication that includes both expressive speaking and supportive listening is a key to helping family members overcome the emotional stress of ambiguous loss. Agreement on every feeling, perception, or plan of action is not necessary but a sense of being safe and being listened to when expressing oneself is important for all family members. Destructive communication, passive aggressive actions, blaming, and open hostility should be avoided to the greatest extent possible. Social support from trusted friends and community groups can be of great assistance. If necessary, outside help from a clergyman or therapist can be not only comforting but growthful as well. Above all, it is important to recognize that the confusion, stress, pain and other complex emotions that often accompany ambiguous loss are real, not imaginary or over-blown. And that open communication and support from others can lead to relief and improved coping.